Meditation Doesn't Work for Me

- Clark R. Mollenhoff III M.Ac., L.Ac.

- Mar 2, 2023

- 8 min read

I often hear people say they are not good at meditation, or “it doesn’t work for me.”

Meditation, at its root, is about familiarizing yourself with the felt experience of your body and mind, and learning to witness the mental activity that is occurring without engaging.

The act of sitting upright with my legs crossed and eyes closed has never made me immediately more peaceful. If anything, trying to breathe deeply and stop my mind from spinning has only increased my level of agitation or suffering.

With enough practice, and when I am practicing regularly, I do experience more peace in my life. This is the result of practicing, but not necessarily the experience of the practice it’s self.

It is when I bring my body to rest and reduce external stimulation that I am faced with myself. All of a sudden there is more thought, more discomfort in my body, more tightness, agitation, stress, etc… Usually this is why I keep moving or keep myself stimulated by something. With stillness comes an onslaught of ideas, judgments, and worries. A tightness in my chest must mean this or that. I am flooded with preferences. I don’t like this, I do like that. I can’t wait to be done with this so I can watch TV or get back to my emails. A beer would be nice. It is at this point that I wonder, “Why am I even doing this?”

If we meditate thinking that we are going to get rid of all this noise, we are likely going to conclude that meditation does not work. Or, at least, it does not work for us. The goal of meditation, as I see it, is to face these uncomfortable voices and sensations. When I am unwilling to face this inner world of emotions and thoughts, my only hope for peace is in escape. In this sense, my ignored inner state drives me towards compulsive action or inaction in the world as a means of anesthetizing the pain I am unwilling to acknowledge or deal with. Simply put, we become predominantly run by our unconscious selves rather than our conscious selves.

From this perspective, the practice of meditation is about bringing awareness into our unconscious self and basically “waking up.” This is what the term “enlightenment” means to me. I don’t see it as a state to reach, but a practice of turning on a light inside. In the beginning, the switch has to be flipped again and again, but as you practice, ideally, the time spent in the dark decreases. It doesn’t mean that someone farther along the continuum of practice can’t become stuck in the darkness. However, the sharper your tools of practice are, the better chance you have of staying out of it.

I realize that using terms like “conscious” and “unconscious” can sound like psychobabble—or vague, new-agey words. But they are the best words I can think of to describe my perspective, and I will do my best to unpack them into more tangible concepts when I can.

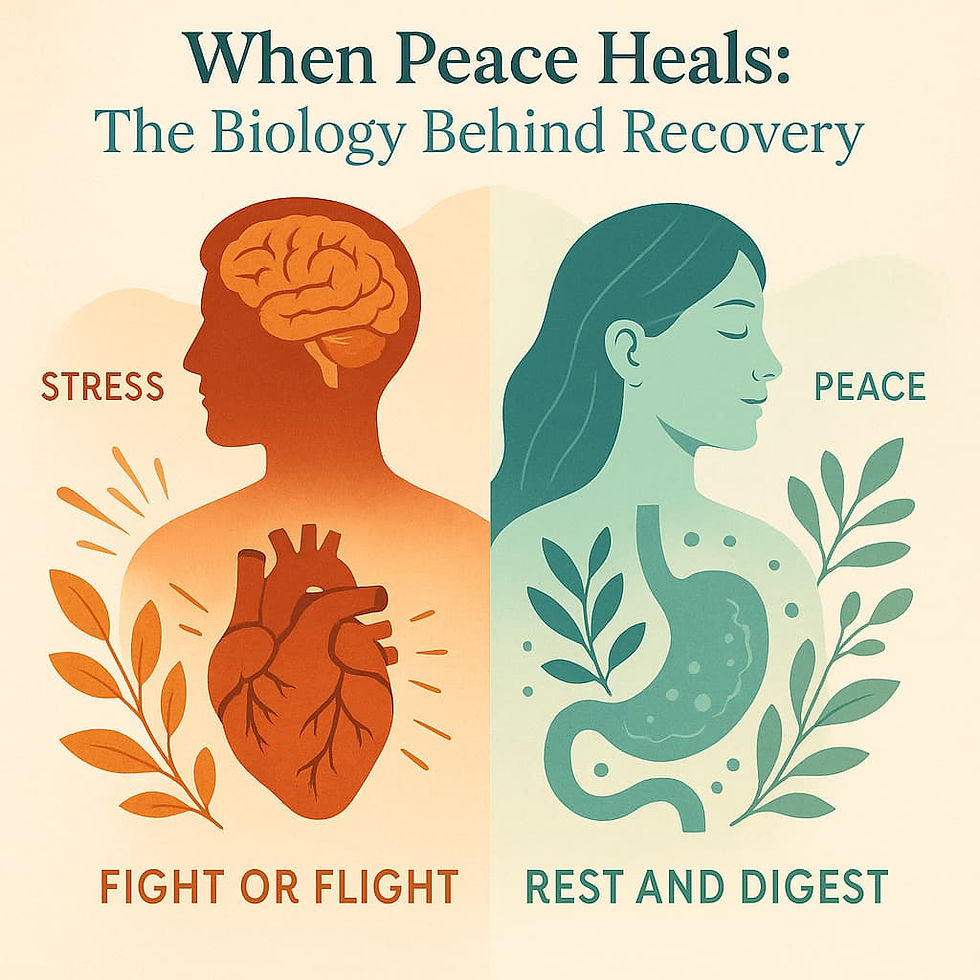

Our breath is the gateway between our autonomic processes and our somatic processes. This is because our breath is controlled below our consciousness, and it is also controlled with our consciousness. If you have experienced a panic attack and tried to do deep breathing, you may have likely experienced the sensation of the panic getting worse as you are unable to override your unconscious rhythm of breathing. The breath is shallow, and any worry or fear about your breathing is likely going to make it shallower, which, in turn, will create more fear. This is the vicious cycle of panic.

The technique I employ in this situation is the foundation for how I engage the practice of meditation. The more you familiarize yourself with a technique during a semi-controlled practice, like meditation, the more likely you will be able to use it in a moment of difficulty. In a relatively normal state of being, I will start the practice with 1-3 deep, conscious breaths, and then I will allow my body to take over and breathe however it does naturally. Then I will practice keeping a gentle observation on my breathing. When I catch my mind wondering, as it certainly will, I bring the attention back to the breath.

In the case of panic, you may not be able to get 1-3 deep, conscious breaths, so I often recommend starting with the second step of allowing the breath to be as shallow as it needs to be.

1) Take 1-3 deep, conscious breaths.

2) Allow natural breathing.

3) Observe natural breathing.

4) Intermittently consciously suggest a deeper breath, and then just observe.

5) Continue observing the natural flow of breath while allowing it to deepen when possible.

The point of this exercise is to begin a conscious dialogue with your inner state. It is a practice of listening and offering. By listening, we allow the body to be as it is, and by offering, we are suggesting another possible way of being. This is where you will often hear a meditation instructor saying to “soften the shoulders, allow the breath to deepen, and breathe into the heart.” The breath allows us to make this connection. It allows us to bring awareness into the depths of ourselves. This is not an easy practice because what we often find are old thoughts, and feelings and struggles that we have been escaping from externally for many years. The only problem is that those old beliefs, and thoughts, and feelings haven’t gone anywhere. In fact, our methods of escaping them have likely become very ingrained into our identities and uncovering them can threaten our sense of self. Why would anyone want to meditate then? It sounds like it could be quite an awful experience. The benefit comes when we begin to change the way we relate to what is uncomfortable or scary in ourselves.

Meditation can become difficult to talk about because ultimately it is a practice of disengaging analysis-type problem-solving, and allowing ourselves to spend time in our senses. It is difficult to talk about because, in the realm of the senses, words are meaningless and so are the thoughts about those words. The moment we put a word to a sense, we are in a thought and no longer purely in the sense. If I say I am angry, I am using a word to hold the place of a deeply complex series of movements and sensations that I am generating in response to something. It may be a very useful and appropriate response in one situation and totally unnecessary in another. The words we use are shorthand for the emotions we experience—not the emotions themselves. As long as I call it “anger,” I can delude myself into thinking that I understand what’s going on. It is also easy to feel as if this “anger” is happening to me, rather than realizing that it is a natural and practiced response, which I have the power to use effectively, or discharge in a way that is not harmful to myself or anyone around me. This empowerment comes from a practice of leaving the words behind in order to explore the world of sensation.

This is where we pick up after step number 5.

6) Practice entering the sensed experience while maintaining a peripheral awareness of the breath.

7) When you realize you are distracted, bring your attention back to the breath or to another sensed experience. This could be sounds, smells, colors, tastes, etc…

8) Explore the world of sense that is actually occurring in that moment.

This part takes some practice. In essence, practicing meditation is a cycle of moving through these steps repeatedly. The felt experience of the present moment is often a foreign one to remain in for very long without interpreting, judging, or documenting the experience from an active mind state. What do we smell or hear? Our inclination will be to label what we smell. (“Oh, that’s lavender!”) But what is the experience of the smell? This is a question to be explored through sense, not answered through description. The categories of words we organize our experiences with, allows us to make sense of our experience. When you taste wine for example, it would be useful to recognize a taste like tobacco or cherry in order to create more sophisticated observation skills. The problem arises when we leave the experience of the flavor and simply say it tastes like cherry. What is the sensed experience of cherry? What kind of internal movement do you notice in your body? We can practice this same type of labeling and observation with our thoughts.

When a thought arises we label it, “Oh that’s a worry thought,” or a fear thought, or an angry thought. In my experience these types of thoughts are paired with uncomfortable feelings somewhere in my body. My instinct tells me to figure out how to not feel this way, leading me to attempt to think my way out of it, or blame something external to myself for the discomfort that is occurring. In many cases this is an accurate response. If there is an actual solution to the problem it is necessary to identify it and make a change. Unfortunately many of our thoughts lie in the future or the past or in a situation or person we have no control over. When these types of thoughts arise and there is no external solution to discharge them, the emotional/biochemical consequences in our bodies build up creating a feed back loop of more negative thoughts. The only ways I am aware of discharging that build up is to become very aware of how my body needs to move, rest, and emote. This is the purpose of labeling the thoughts, then moving attention beneath to the felt physical experience. What does anger or anxiety feel like? What does my body need from me?

From an intellectual perspective it may be clear that our stress is the result of someone else’s behavior or choices, or even our current life circumstances. We may even feel certain that we have a genetic predisposition to feeling a certain way. Any of these explanations may be true, but as long as we perceive that our inner state is at the mercy of our environment or our genetics we will have no power in changing that experience. The most important step is to take responsibility for our own internal response to our lives.

We have a capacity for an infinite number of thoughts in any given moment. How do we choose which thoughts we will engage and which ones we let drift on by? In meditation, we practice not engaging any of the thoughts that occur. This takes away the need to assign a judgment or preference over the thoughts, and in effect, takes away the charge that hooks us. This practice is not intended to make us non-thinking sense-organisms, it is meant to allow us the freedom to choose which thoughts are useful to cultivate and which ones create unnecessary suffering in our lives.

Meditation is not a practice used to banish the pain from our lives, it is about the courage to actually feel it and learn from it instead of intellectualizing it or running from it. When I have the courage to sit and feel and breathe, I am faced with myself as I am in that moments. If I have the patience to stay with my breath long enough, I might feel discomfort. I might cry. I might notice how tight I am in my body. I might deepen my breath. I might accept something I was fighting. I might remember something in my heart. I might offer myself or someone else some compassion. I might even forgive myself.

Comments